Poem

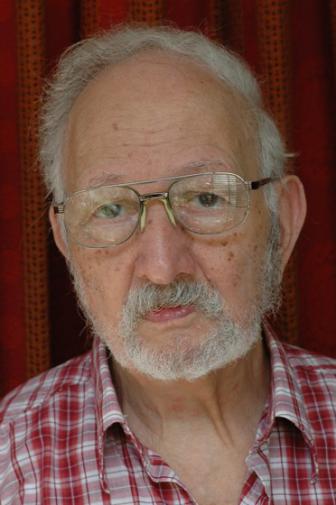

Aharon Almog

SAROYAN IS DEAD

Saroyan is dead.An Armenian writer with a nose that protrudes in sadness.

The most Jewish nose I know.

At the Sha’arey Tsiyon municipal library on Montefiore street I

deposited all my savings for a selection of his short stories

and that same day I came back to get The Human Comedy.

The librarian scowled at me and said it was against regulations and I

brought him my uncle who was a welder in Yafo-Tel Aviv

hoping to strike fear into him.

My uncle came in blue overalls looked around and surprisingly

fell silent, he thought and thought looked at the ceiling looked at the librarian

and said: Train up a lad in the way he should go.*

That was the most intelligent sentence my uncle ever spoke.

I left with The Human Comedy cheering all the way.

The coachmen on Herzl street saw me cheering. Toscanini the cop

directing traffic asked me not to disturb the residents’ rest.

You see, said my uncle, brother of my mother:

A gentle tongue breaks a bone.*

That summer day of 1940 on 85 Herzl Street I got to know

all the Armenians in San Fernando and San Yehoyahin valleys, I met Aram

and his uncle Misak who like my uncle was a strong man, and Arak his son, and his

nephew Mourad and his mother and nephew and cousins and talkative Dikran.

But most of all I was bound by bonds of love to Homer who always asked for

things no-one could afford: a fountain pen, roller skates, soccer shoes.

I too asked for similar things and got slapped across the face and so I came

with William Saroyan to the primary school in Neve Tsedek with swollen cheeks and

boxed ears. I sat in class, my eyes darting, trying to acquire wisdom and learning.

The English teacher went and told the principal that I was blinking during class.

The principal called me into his room and watched me for a long

while hoping to catch me in the act.

I stood for three hours not batting an eyelid as I imagined myself

running on the streets of San Francisco with The Saturday Evening Post.

My standing there like a fool left a huge impression.

Posthaste I was sent to the psychologist

who sent me with a note back to my school in Neve Tsedek.

This is the right place for him determined the psychologist.

I did not return to the library.

Hidden forces romped within me.

I played soccer and sang in the Great Synagogue’s choir, secretly dreaming

of being a telegram-singing mailman. I had a soprano, God help us, a shriek

that denied sleep to the denizens of Nahalat Binyamin.

Then came years of decline with William Saroyan at the height of his ability.

In America they don’t like Armenians that’s nothing new, here

they don’t either. Just look at them those conceited hot air balloons

who read about love in books and their childhood was spat out by computers with

the salary slips. They’ve never heard of you. That’s what they look like.

A human comedy.

© Translation: 2021, Itamar Francez

Train up a lad in the way he should go. Proverbs 22:6

A gentle tongue breaks a bone. Proverbs 25:15

Translation by Robert Alter

SAROYAN IS DEAD

© 2004, Aharon Almog

From: If You See a Sukkah Flying

Publisher: Hakibbutz Hameuchad, Tel Aviv

From: If You See a Sukkah Flying

Publisher: Hakibbutz Hameuchad, Tel Aviv

Poems

Poems of Aharon Almog

Close

SAROYAN IS DEAD

Saroyan is dead.An Armenian writer with a nose that protrudes in sadness.

The most Jewish nose I know.

At the Sha’arey Tsiyon municipal library on Montefiore street I

deposited all my savings for a selection of his short stories

and that same day I came back to get The Human Comedy.

The librarian scowled at me and said it was against regulations and I

brought him my uncle who was a welder in Yafo-Tel Aviv

hoping to strike fear into him.

My uncle came in blue overalls looked around and surprisingly

fell silent, he thought and thought looked at the ceiling looked at the librarian

and said: Train up a lad in the way he should go.*

That was the most intelligent sentence my uncle ever spoke.

I left with The Human Comedy cheering all the way.

The coachmen on Herzl street saw me cheering. Toscanini the cop

directing traffic asked me not to disturb the residents’ rest.

You see, said my uncle, brother of my mother:

A gentle tongue breaks a bone.*

That summer day of 1940 on 85 Herzl Street I got to know

all the Armenians in San Fernando and San Yehoyahin valleys, I met Aram

and his uncle Misak who like my uncle was a strong man, and Arak his son, and his

nephew Mourad and his mother and nephew and cousins and talkative Dikran.

But most of all I was bound by bonds of love to Homer who always asked for

things no-one could afford: a fountain pen, roller skates, soccer shoes.

I too asked for similar things and got slapped across the face and so I came

with William Saroyan to the primary school in Neve Tsedek with swollen cheeks and

boxed ears. I sat in class, my eyes darting, trying to acquire wisdom and learning.

The English teacher went and told the principal that I was blinking during class.

The principal called me into his room and watched me for a long

while hoping to catch me in the act.

I stood for three hours not batting an eyelid as I imagined myself

running on the streets of San Francisco with The Saturday Evening Post.

My standing there like a fool left a huge impression.

Posthaste I was sent to the psychologist

who sent me with a note back to my school in Neve Tsedek.

This is the right place for him determined the psychologist.

I did not return to the library.

Hidden forces romped within me.

I played soccer and sang in the Great Synagogue’s choir, secretly dreaming

of being a telegram-singing mailman. I had a soprano, God help us, a shriek

that denied sleep to the denizens of Nahalat Binyamin.

Then came years of decline with William Saroyan at the height of his ability.

In America they don’t like Armenians that’s nothing new, here

they don’t either. Just look at them those conceited hot air balloons

who read about love in books and their childhood was spat out by computers with

the salary slips. They’ve never heard of you. That’s what they look like.

A human comedy.

© 2021, Itamar Francez

From: If You See a Sukkah Flying

From: If You See a Sukkah Flying

SAROYAN IS DEAD

Saroyan is dead.An Armenian writer with a nose that protrudes in sadness.

The most Jewish nose I know.

At the Sha’arey Tsiyon municipal library on Montefiore street I

deposited all my savings for a selection of his short stories

and that same day I came back to get The Human Comedy.

The librarian scowled at me and said it was against regulations and I

brought him my uncle who was a welder in Yafo-Tel Aviv

hoping to strike fear into him.

My uncle came in blue overalls looked around and surprisingly

fell silent, he thought and thought looked at the ceiling looked at the librarian

and said: Train up a lad in the way he should go.*

That was the most intelligent sentence my uncle ever spoke.

I left with The Human Comedy cheering all the way.

The coachmen on Herzl street saw me cheering. Toscanini the cop

directing traffic asked me not to disturb the residents’ rest.

You see, said my uncle, brother of my mother:

A gentle tongue breaks a bone.*

That summer day of 1940 on 85 Herzl Street I got to know

all the Armenians in San Fernando and San Yehoyahin valleys, I met Aram

and his uncle Misak who like my uncle was a strong man, and Arak his son, and his

nephew Mourad and his mother and nephew and cousins and talkative Dikran.

But most of all I was bound by bonds of love to Homer who always asked for

things no-one could afford: a fountain pen, roller skates, soccer shoes.

I too asked for similar things and got slapped across the face and so I came

with William Saroyan to the primary school in Neve Tsedek with swollen cheeks and

boxed ears. I sat in class, my eyes darting, trying to acquire wisdom and learning.

The English teacher went and told the principal that I was blinking during class.

The principal called me into his room and watched me for a long

while hoping to catch me in the act.

I stood for three hours not batting an eyelid as I imagined myself

running on the streets of San Francisco with The Saturday Evening Post.

My standing there like a fool left a huge impression.

Posthaste I was sent to the psychologist

who sent me with a note back to my school in Neve Tsedek.

This is the right place for him determined the psychologist.

I did not return to the library.

Hidden forces romped within me.

I played soccer and sang in the Great Synagogue’s choir, secretly dreaming

of being a telegram-singing mailman. I had a soprano, God help us, a shriek

that denied sleep to the denizens of Nahalat Binyamin.

Then came years of decline with William Saroyan at the height of his ability.

In America they don’t like Armenians that’s nothing new, here

they don’t either. Just look at them those conceited hot air balloons

who read about love in books and their childhood was spat out by computers with

the salary slips. They’ve never heard of you. That’s what they look like.

A human comedy.

© 2021, Itamar Francez

Sponsors