Poem

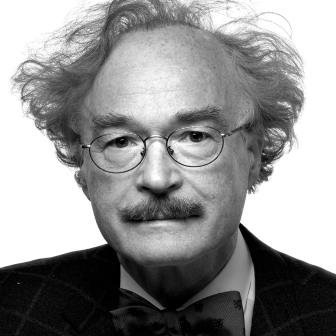

Knut Ødegård

DRUNKARDS AND CRAZY FOLK

The drunkards, with splendid namessuch as Konrad or Adolf, gathered together

on the outskirts of Molde. Sometimes their singing

was borne on the wind to us: old hits

or sad low-church hymns about the cross

and Jesus’ bleeding side. The crazy folk too

wandered around on the outskirts – people like Lundli, who had

once got his intermediary-school diploma: at night, he hewed

and sawed heavy trees, the sound cut its way into the sleep

of us children and got mixed up with dreams

about flying over the housetops or drawing up big fish

from pools with infinite darkening depths

One day, his cross finished, Lundli went

slowly at evening in his white sheet along the High Street

with the huge cross slung over his back.

After him followed the drunkards, Konrad, Adolf

and the rest, and then a throng of children: I kept

my fingers tight around the chestnut from the cemetery tree in my pocket.

Lundli called out in his light tenor and falsetto YOU MUST TAKE

UP YOUR CROSS AND FOLLOW ME SAYS THE LORD! His words

flew like fire to Konrad and Adolf, their big

drunkards’ lips replied: “Follow me, says the Lord!

And Hallelujah! And Hallelujah!” Their white hands

danced like wings in the air

The pentecostal procession passed the Alexandra Hotel.

In the windows of the wine bar were the pink faces of queers

and elderly divorcees: in his alcoholic stupor, gay

Jens in his checked sailor suit and tie stumbled down the steps

from the hotel and joined in the procession. Old Hansen the

tinsmith, divorced for thirty years, with his heart full

of spittle from his own children, took his time, but

followed him and glided in the crumpled wedding-suit

that was too tight for him, his belly wobbling: he followed

right behind crazy Lundli, who sang FOLLOW ME

FOLLOW ME SAYS THE LORD FOR IT IS NOT THE HEALTHY

WHO NEED THE PHYSICIAN BUT THOSE WHO ARE SICK

OF SIN COME ALL YOU WHO HAVE SINNED and from the

direction of the quay came the clattering steps of skinny old Karen,

whose going price was a pail of beer and who knew

the town’s trouser buttons and zips better than the cheerful

seamstresses: she emerged from the shack and the toilet on the quay

and drifted into the procession

Crazy Lundli was almost collapsing

under the enormous cross he had carved out

and assembled in the long dark nights, hammering it

firmly into place with rusty nails left by the German occupation.

From far away came deep rumbles, and lightning cut across the skies:

now the procession glided on to the town square and the clouds amassed

over the heads of the drunkards and crazy folk, children and queers

and divorcees and women of doubtful repute who cried out: “Hallelujah!

Praise the Lord!” as the first raindrops

squirted on to Lundli’s bald pate. The vicar made an appearance

in his black robes, and the police in full uniform

and nurses in white took care of Lundli: they jabbed

syringes into him as he cried through the rain and the wind

PRAISE THE LORD ALL SINNERS FOR HIS GRACE UPON GRACE

TAKE UP THE CROSS AND FOLLOW THE LORD. Then he turned white

and fainted in the ambulance while Konrad and Adolf

held the cross firmly upright in the rainstorm in Molde

The vicar in his black gown got up

on Lundli’s margarine crate on the town square: “Go home!”

he commanded, “this is delusion, sickness, indeed

minds gone mad. Jesus did not mean it literally

when he talked about crosses, it was symbolic and

referred to ‘burdens’ as a theoretical concept,” cried the priest

from the crazy man’s crate. Then the heavens burst open

above Molde and lightning cut a path through the darkness

like a blazing arrow towards the church tower: the bells began

to ring torrential peals, indeed the earth trembled and now the

rain was coming down like Noah’s floodwater. I squelched home

in big boots, taking the shortcut across the cemetery,

snatching up the chestnuts, which flowed in their green shells

from grave to grave

and after slices of bread with margarine and syrup

came the night with its dreams to us children

and to crazy folk and sinners: we flew without wings

over the town, mounting steeply like a flock of birds

with crazy Lundli and his cross at our head, rising

up to a heaven where big fish squirmed up

from bottomless depths of darkness

© Translation: 2013, Brian McNeil

ZUIPLAPPEN EN MALLOTEN

De zuiplappen, met fraaie namenals Konrad of Adolf, die hielden zich op

aan de rand van Molde. Soms dreef hun gezang

op de wind naar ons toe: oude schlagers

of trieste kerkliederen over kruis

en bloedende zijdewonden. Ook de gekken

zwierven daar rond, Lundli bijv. die ooit

nog de middenschool gedaan had: ’s nachts hakte en

zaagde hij in grote bomen, het geluid sneed zich de slaap

van ons kinderen binnen, vermengde zich met dromen

van over de daken vliegen of grote vissen ophalen

uit meertjes vol eindeloos diepe duisternis

Op een dag was zijn kruis klaar, Lundli liep

langzaam in zijn witte lakens door Storgata

met het enorme kruis op zijn rug.

Achter hem volgden de zuiplappen, Konrad, Adolf

en de anderen, en daarna een stroom kinderen: ik omklemde

de kastanje van de boom op het kerkhof stevig in mijn broekzak.

Lundli riep met lichte tenor en falset NEEM JE KRUIS OP

EN VOLG MIJ ZEGT DE HEER! Zijn woorden

flikkerden als vuur naar Konrad en Adolf, hun grote

dronkaardslippen antwoordden: Volg mij, zegt de Heer!

En Halleluja! En Halleluja! Hun witte handen

dansten als vleugels in de lucht

De lijdensstoet passeerde hotel Alexandra.

In de ramen van de wijnbar de rossige gezichten van nichten

en gescheiden ouderen: beneveld struikelde homo

Jens in zijn geruite verkoperspak en das de trap

van het hotel af en sloot zich bij de stoet aan. De oude blik-

slager Hansen, al dertig jaar gescheiden, zijn hart vol

met gespuug van zijn eigen kinderen, kwam sloom

aangegleden in zijn omgekrulde al te

strakke huwelijkspak en deinende buik: volgde

de gek Lundli op de voet, die zong VOLG MIJ

VOLG MIJ ZEGT DE HEER WIE GEZOND ZIJN

hebben geen dokter nodig maar WIE ZIEK ZIJN

VAN ZONDE KomT ALLEN DIE GEZONDIGD HEBBEN en vanaf

de kade kwam magere, oude Karen aanrammelen, die

zich voor een pot bier liet nemen en die

de broeksknopen ritssluitingen in de stad beter kende dan de vrolijke

naaisters: uit schuur en kadegoot kwam ze

aanwapperen en sloot zich aan

Malloot Lundli bezweek bijna

onder het enorme kruis dat hij in lange donkere nachten

in elkaar getimmerd en gesneden had, vastgehamerd

met verroeste spijkers, nog van de Duitsers. Uit de verte

klonk diep gedreun en bliksem doorkliefde de hemel: de stoet

gleed de markt op en de wolken stonden dicht

boven de zuiplappen en malloten, kinderen en nichten

gescheiden mannen en twijfelachtige vrouwen die halleluja!

prijs de heer! riepen terwijl de eerste regendruppels

op Lundli spatten, z’n kale schedel. Daar was

de dominee in het zwart en de politie in vol ornaat

en verplegers in het wit bekommerden zich om Lundli: spoten

hem plat terwijl hij door weer en wind riep

PRIJS DE HEER ALLE ZONDAARS VOOR ZIJN GENADE OP GENADE

NEEM JE KRUIS OP EN VOLG DE HEER. Toen verbleekte hij

en verdween in de ambulance terwijl Konrad en Adolf

het kruis overeind hielden in het onweer in Molde

De dominee in het zwart klom op

de markt op Lundli’s zeepkist: Ga naar huis!

gebood hij, dit is dwaling en ziekelijk, ja

verwrongen geesten. Jezus bedoelde het niet

letterlijk als hij het had over kruisen, het was

symbolisch, overdrachtelijke lasten, riep de dominee

vanaf de zeepkist van de malloot. Toen brak de hemel

boven Molde open en bliksem kliefde door de duisternis, als een

vlammende pijl op de kerktoren af: de klokken begonnen

als een gek te luiden, ja de aarde beefde en als een zondvloed

kwam de regen. Ik sopte naar huis in grote laarzen,

nam de kortste weg over het kerkhof, greep nog

wat kastanjes mee die in hun groene bolsters

van graf naar graf dreven

en na de boterhammen met margarine en stroop

kwam de nacht met zijn dromen tot ons kinderen

en malloten en zondaars: we vlogen zonder vleugels

over de stad, stegen schuin op als een vogelzwerm

met gekke Lundli en zijn kruis voorop, stegen op

naar een hemel waar grote vissen tevoorschijn spartelden

uit bodemloos diepe duisternis

© Vertaling: 2013,

DRANKARAR OG GALNINGAR

Drankarane, med flotte namnsom Konrad eller Adolf, dei heldt seg

i utkanten av Molde by. Stundom dreiv songen deira

med vinden mot oss: Gamle schlagerar

eller triste bedehussongar um kross

og blødande sidesår. I utkanten flakka òg

dei galne ikring, Lundli t.d. som ein gong

hadde teke middelskulen: Um netene hogg han

og saga i store tre, lyden skar seg inn i svevnen

til oss born, blanda seg med draumar

um å flyga yver hustak eller draga store fiskar upp

frå tjern som myrkna endelaust nedyver

Ein dag var krossen hans ferdig, Lundli gjekk

seint i sine kvite laken gjennom Storgata

med den veldige krossen yver ryggen.

Etter han fylgde drankarane, Konrad, Adolf

og dei andre, og so ein skokk med born: Eg heldt

stramt um kastanjen frå kyrkjegardstreet i lomma.

Lundli ropte i ljos tenor og fistel DU SKAL TAKA

DIN KROSS UPP OG FYLGJA MEG SEGJER HERREN! Ordi hans

fauk som eld mot Konrad og Adolf, dei store

drankarlippene deira svara: Fylg meg, segjer Herren!

Og Halleluja! Og Halleluja! Dei kvite hendene deira

dansa som venger i lufti

Pinsletoget passerte hotell Alexandra.

I vinstova stod dei rosa andleta til soparar

og gamle fråskilde i vindauga: I rus ramla soparen

Jens i rutete seljardress og slips ned trappene

frå hotellet og slutta seg til toget. Gamle blikken-

slagar Hansen, fråskild i tretti år, med hjarta fullt

av spytt frå sine eigne born, kom seint

glidande etter i sin krøllete altfor

tronge bryllaupsdress og dissande mage: Gjekk hakk

i hæl med galningen Lundli som song FYLG MEG

FYLG MEG SEGJER HERREN FOR DEI FRISKE

TRENG IKKJE TIL LÆKJAR MEN DEI SOM ER SJUKE

AV SYND KOM ALLE KOM DE SOM HEV SYNDA og ut frå

kaia kom gamle jenta Karen skranglande mager, ho

som vart seld for eit spann øl og som kjende

byens bukseknappar glidelås betre enn dei lystige

syerskene: Ut frå skur og kaikloakken kom ho

flaksande inn i toget

Galningen Lundli var nær ved å siga saman

under den veldige krossen han hadde skore

og snikra saman i lange myrke netter, hamra

fast med rustne spikrar etter tyskarane. Langt

burtefrå kom djupe drøn og lyn skar yver himmelen: No

gleid toget inn på torget og skyene stod tett

yver drankarar og galningar, born og soparar

og fråskilde og tvilsame kvinner som ropte halleluja!

pris Herren! i det dei fyrste regndropane

skvatt mot Lundli, hans blanke skalle. Der var

soknepresten møtt i svart og politi i full mundur

og pleiarar i kvitt tok hand um Lundli: Stakk

sprøyter i han då han ropte gjennom regn og vind

PRIS HERREN ALLE SYNDARAR FOR HANS NÅDE YVER NÅDE

TAK KROSSEN UPP FYLG HERREN. So bleikna han

og kvarv i ambulansen medan Konrad og Adolf

heldt krossen støtt i uvêret i Molde by

Soknepresten steig i svarte klede upp

på margarinkassa til Lundli på torget: Gå heim!

baud han, dette er villfaring, sjukdom, ja

forrykte sinn. Jesus meinte ingen ting

bokstavleg med sitt snakk um krossar, symbolsk

var det og tenkte byrder, ropte presten ut

frå kassa til den galne. Då brast himmelen

yver molde by og lyn skar gjennom myrkret som ei

logande pil mot kyrkjetårnet: Klokkene sette i

å fossringja, ja jordi skalv og som ein Noa-flaum

kom regnet no. Eg surkla heim i store støvlar,

fór snarvegen yver kyrkjegarden, snappa med meg

kastanjene som flaut i sine grøne skal

frå grav til grav

og etter brødskiver med margarin og sirup

kom natti med sine draumar til oss born

og galningar og syndarar: Vi flaug utan venger

yver byen, steig skrått som eit fugletrekk

med galningen Lundli og hans kross i brodden, steig

mot ein himmel der store fiskar sprella fram

frå botnlause djup av myrker

© 2005, Knut Ødegård

From: Kringsjå

Publisher: J.W. Cappelens Forlag, Oslo

From: Kringsjå

Publisher: J.W. Cappelens Forlag, Oslo

Poems

Poems of Knut Ødegård

Close

DRUNKARDS AND CRAZY FOLK

The drunkards, with splendid namessuch as Konrad or Adolf, gathered together

on the outskirts of Molde. Sometimes their singing

was borne on the wind to us: old hits

or sad low-church hymns about the cross

and Jesus’ bleeding side. The crazy folk too

wandered around on the outskirts – people like Lundli, who had

once got his intermediary-school diploma: at night, he hewed

and sawed heavy trees, the sound cut its way into the sleep

of us children and got mixed up with dreams

about flying over the housetops or drawing up big fish

from pools with infinite darkening depths

One day, his cross finished, Lundli went

slowly at evening in his white sheet along the High Street

with the huge cross slung over his back.

After him followed the drunkards, Konrad, Adolf

and the rest, and then a throng of children: I kept

my fingers tight around the chestnut from the cemetery tree in my pocket.

Lundli called out in his light tenor and falsetto YOU MUST TAKE

UP YOUR CROSS AND FOLLOW ME SAYS THE LORD! His words

flew like fire to Konrad and Adolf, their big

drunkards’ lips replied: “Follow me, says the Lord!

And Hallelujah! And Hallelujah!” Their white hands

danced like wings in the air

The pentecostal procession passed the Alexandra Hotel.

In the windows of the wine bar were the pink faces of queers

and elderly divorcees: in his alcoholic stupor, gay

Jens in his checked sailor suit and tie stumbled down the steps

from the hotel and joined in the procession. Old Hansen the

tinsmith, divorced for thirty years, with his heart full

of spittle from his own children, took his time, but

followed him and glided in the crumpled wedding-suit

that was too tight for him, his belly wobbling: he followed

right behind crazy Lundli, who sang FOLLOW ME

FOLLOW ME SAYS THE LORD FOR IT IS NOT THE HEALTHY

WHO NEED THE PHYSICIAN BUT THOSE WHO ARE SICK

OF SIN COME ALL YOU WHO HAVE SINNED and from the

direction of the quay came the clattering steps of skinny old Karen,

whose going price was a pail of beer and who knew

the town’s trouser buttons and zips better than the cheerful

seamstresses: she emerged from the shack and the toilet on the quay

and drifted into the procession

Crazy Lundli was almost collapsing

under the enormous cross he had carved out

and assembled in the long dark nights, hammering it

firmly into place with rusty nails left by the German occupation.

From far away came deep rumbles, and lightning cut across the skies:

now the procession glided on to the town square and the clouds amassed

over the heads of the drunkards and crazy folk, children and queers

and divorcees and women of doubtful repute who cried out: “Hallelujah!

Praise the Lord!” as the first raindrops

squirted on to Lundli’s bald pate. The vicar made an appearance

in his black robes, and the police in full uniform

and nurses in white took care of Lundli: they jabbed

syringes into him as he cried through the rain and the wind

PRAISE THE LORD ALL SINNERS FOR HIS GRACE UPON GRACE

TAKE UP THE CROSS AND FOLLOW THE LORD. Then he turned white

and fainted in the ambulance while Konrad and Adolf

held the cross firmly upright in the rainstorm in Molde

The vicar in his black gown got up

on Lundli’s margarine crate on the town square: “Go home!”

he commanded, “this is delusion, sickness, indeed

minds gone mad. Jesus did not mean it literally

when he talked about crosses, it was symbolic and

referred to ‘burdens’ as a theoretical concept,” cried the priest

from the crazy man’s crate. Then the heavens burst open

above Molde and lightning cut a path through the darkness

like a blazing arrow towards the church tower: the bells began

to ring torrential peals, indeed the earth trembled and now the

rain was coming down like Noah’s floodwater. I squelched home

in big boots, taking the shortcut across the cemetery,

snatching up the chestnuts, which flowed in their green shells

from grave to grave

and after slices of bread with margarine and syrup

came the night with its dreams to us children

and to crazy folk and sinners: we flew without wings

over the town, mounting steeply like a flock of birds

with crazy Lundli and his cross at our head, rising

up to a heaven where big fish squirmed up

from bottomless depths of darkness

© 2013, Brian McNeil

From: Kringsjå

From: Kringsjå

DRUNKARDS AND CRAZY FOLK

The drunkards, with splendid namessuch as Konrad or Adolf, gathered together

on the outskirts of Molde. Sometimes their singing

was borne on the wind to us: old hits

or sad low-church hymns about the cross

and Jesus’ bleeding side. The crazy folk too

wandered around on the outskirts – people like Lundli, who had

once got his intermediary-school diploma: at night, he hewed

and sawed heavy trees, the sound cut its way into the sleep

of us children and got mixed up with dreams

about flying over the housetops or drawing up big fish

from pools with infinite darkening depths

One day, his cross finished, Lundli went

slowly at evening in his white sheet along the High Street

with the huge cross slung over his back.

After him followed the drunkards, Konrad, Adolf

and the rest, and then a throng of children: I kept

my fingers tight around the chestnut from the cemetery tree in my pocket.

Lundli called out in his light tenor and falsetto YOU MUST TAKE

UP YOUR CROSS AND FOLLOW ME SAYS THE LORD! His words

flew like fire to Konrad and Adolf, their big

drunkards’ lips replied: “Follow me, says the Lord!

And Hallelujah! And Hallelujah!” Their white hands

danced like wings in the air

The pentecostal procession passed the Alexandra Hotel.

In the windows of the wine bar were the pink faces of queers

and elderly divorcees: in his alcoholic stupor, gay

Jens in his checked sailor suit and tie stumbled down the steps

from the hotel and joined in the procession. Old Hansen the

tinsmith, divorced for thirty years, with his heart full

of spittle from his own children, took his time, but

followed him and glided in the crumpled wedding-suit

that was too tight for him, his belly wobbling: he followed

right behind crazy Lundli, who sang FOLLOW ME

FOLLOW ME SAYS THE LORD FOR IT IS NOT THE HEALTHY

WHO NEED THE PHYSICIAN BUT THOSE WHO ARE SICK

OF SIN COME ALL YOU WHO HAVE SINNED and from the

direction of the quay came the clattering steps of skinny old Karen,

whose going price was a pail of beer and who knew

the town’s trouser buttons and zips better than the cheerful

seamstresses: she emerged from the shack and the toilet on the quay

and drifted into the procession

Crazy Lundli was almost collapsing

under the enormous cross he had carved out

and assembled in the long dark nights, hammering it

firmly into place with rusty nails left by the German occupation.

From far away came deep rumbles, and lightning cut across the skies:

now the procession glided on to the town square and the clouds amassed

over the heads of the drunkards and crazy folk, children and queers

and divorcees and women of doubtful repute who cried out: “Hallelujah!

Praise the Lord!” as the first raindrops

squirted on to Lundli’s bald pate. The vicar made an appearance

in his black robes, and the police in full uniform

and nurses in white took care of Lundli: they jabbed

syringes into him as he cried through the rain and the wind

PRAISE THE LORD ALL SINNERS FOR HIS GRACE UPON GRACE

TAKE UP THE CROSS AND FOLLOW THE LORD. Then he turned white

and fainted in the ambulance while Konrad and Adolf

held the cross firmly upright in the rainstorm in Molde

The vicar in his black gown got up

on Lundli’s margarine crate on the town square: “Go home!”

he commanded, “this is delusion, sickness, indeed

minds gone mad. Jesus did not mean it literally

when he talked about crosses, it was symbolic and

referred to ‘burdens’ as a theoretical concept,” cried the priest

from the crazy man’s crate. Then the heavens burst open

above Molde and lightning cut a path through the darkness

like a blazing arrow towards the church tower: the bells began

to ring torrential peals, indeed the earth trembled and now the

rain was coming down like Noah’s floodwater. I squelched home

in big boots, taking the shortcut across the cemetery,

snatching up the chestnuts, which flowed in their green shells

from grave to grave

and after slices of bread with margarine and syrup

came the night with its dreams to us children

and to crazy folk and sinners: we flew without wings

over the town, mounting steeply like a flock of birds

with crazy Lundli and his cross at our head, rising

up to a heaven where big fish squirmed up

from bottomless depths of darkness

© 2013, Brian McNeil

Sponsors