Article

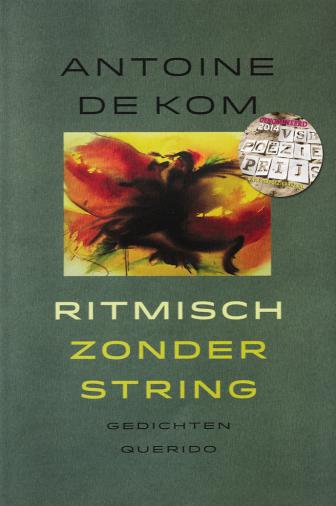

rhythmic no string – Antoine de Kom (Querido, 2013)

rhythmic no string

November 18, 2013

first there were children later

the soldiers came and fired in the sand.

chairs fell over.

your blank sheets had gone.

you spoke although the shooting had stopped.

you spoke to the soldiers in the local language.

the children stand silent to the side.

then the rain’s there again

there are leaves again from which you emerge.

you’re probably thinking of it all again

when you come sighing from the focal point very close

beside me

then you whisper in jest

that you were a fairy and I was a gnome.

a rather silly

gnome with a fat paunch and a little

white beard and almost naked except for one thing:

this ribbon of white sheets floating from my left

to my right hand.

In 1991, twenty years after returning from Suriname, the poet made his debut with the collection Tropen (‘Tropics’) which was immediately nominated for the C. Buddingh’ Prijs, an annual award for new Dutch poets and their poetry. In his poems the world is multi-coloured, the sun shines brightly in the sky, there are hummingbirds and mahogany trees and hardly a sound can be heard in the oppressive heat that induces such lethargy. The title of De Kom’s collection is not simply a reference to the geographical region of his teenage years. It is also an allusion to the trope, the figure of speech employed to add texture to his work and to the way in which he succeeds in enriching the language by giving new meanings to new words.

The defining role played by ambiguity and matters linked to identity permeates all of De Kom’s work, both in his daily work and in his poetic career. In a recent interview he explained how, possibly precisely because of his confusing identity, he feels a kind of affinity with people who have at one time or another found themselves in strange situations. These are the kinds of people with whom De Kom regularly comes into contact during the course of his work as a forensic psychiatrist in the Pieter Baan Centre. Reflecting on the matter of the relationship that a psychiatrist has with his patients, he has published a collection of fictitious discussions between historical criminal figures, such as the emperor Nero and Osama Bin Laden, in the book Het misdadige brein. Over het kwaad in onszelf (‘The criminal brain. About the evil in oneself’). In terms of his poetic self De Kom has sometimes compared himself to a ‘white raven’. His grandfather, Anton de Kom, who spoke out in support of the slaves and the black community in Suriname, was black. Since Anton de Kom married a white woman and Antoine de Kom’s own mother was also white, the poet is much paler than many Surinamers. This subject, the matter of the different colours of the skins of the people in his family, returns in his second collection De kilte in Brasilia (‘The chilliness of Brasilia’; 1995). Even the title of the collection Zebrahoeven (‘Zebra’s hooves’; 2001) reminds one of the connection that exists between black and white.

In an interview De Kom once revealed that because of his skin colour he is often presumed to be someone who hails from the Mediterranean region. In fact it would seem that De Kom feels rather at home in those parts: his most recent collection, ritmisch zonder string (‘rhythmic no string’), includes many references to visits made to countries around the Mediterranean Sea. He has written poems in Fes, Menorca, Istanbul and Damascus that allude to the presidential Syrian family and relate to the Sahara. However, De Kom has also travelled to places such as Honduras, Cape Town and Hawaii. Just as in his previous collections, he tends to ignore traditional verse forms. On the other hand De Kom does, so he claims, deliberately try to push back the barriers of poetry. He achieves that by composing prose poems, poems that read like email messages and, for instance, through the long cycle with the title Sahara Sand comprising four-lined stanzas and incorporating drawings by Julie Dassaud. It is work that displays great dedication, however De Kom confesses to having in the past been careful not to allow the message to gain the upper hand as can often happen in Surinamese poetry. ‘With me the aesthetic always has to hit back at the ethical aspect.’

It is precisely that coming together of engagement and aesthetics, the ‘making tangible of many strange worlds by combining the sensory and powerful quality of visual language with slang and folklore’ that is so highly prized by the 2014 VSB Poetry Prize jury.

Antoine de Kom makes many strange worlds virtually tangible by combining the sensory and powerful quality of visual language with slang and folklore. It is in those worlds that his language explodes to variously wash like waves, leap from pillar to post or abruptly come to a halt. At the same time, De Kom reveals a deeply anchored type of involvement. It prompts him to draw attention to harsh reality and to – happily – mock the role of the poet. In fact his poetry is all about ‘reflecting on what is still to come’.

first there were children later

the soldiers came and fired in the sand.

chairs fell over.

your blank sheets had gone.

you spoke although the shooting had stopped.

you spoke to the soldiers in the local language.

the children stand silent to the side.

then the rain’s there again

there are leaves again from which you emerge.

you’re probably thinking of it all again

when you come sighing from the focal point very close

beside me

then you whisper in jest

that you were a fairy and I was a gnome.

a rather silly

gnome with a fat paunch and a little

white beard and almost naked except for one thing:

this ribbon of white sheets floating from my left

to my right hand.

Antoine de Kom

from ritmisch zonder string

(translation by Paul Vincent)

Antoine de Kom was born in The Hague in 1956 but spent his formative years in Paramaribo. From the age of ten until the age of fifteen he discovered there how great the difference can be between one’s idea of oneself and one’s actual image, he was surprised to discover how many people viewed him, grandson of Anton de Kom – famous campaigner for the black people’s cause – as a ‘white Dutchman’. In the words of De Kom: ‘My identity is much darker than the way I look’. It is the identity issue, coupled with his years in the tropics, that really forms the central themes in the work of De Kom.from ritmisch zonder string

(translation by Paul Vincent)

In 1991, twenty years after returning from Suriname, the poet made his debut with the collection Tropen (‘Tropics’) which was immediately nominated for the C. Buddingh’ Prijs, an annual award for new Dutch poets and their poetry. In his poems the world is multi-coloured, the sun shines brightly in the sky, there are hummingbirds and mahogany trees and hardly a sound can be heard in the oppressive heat that induces such lethargy. The title of De Kom’s collection is not simply a reference to the geographical region of his teenage years. It is also an allusion to the trope, the figure of speech employed to add texture to his work and to the way in which he succeeds in enriching the language by giving new meanings to new words.

The defining role played by ambiguity and matters linked to identity permeates all of De Kom’s work, both in his daily work and in his poetic career. In a recent interview he explained how, possibly precisely because of his confusing identity, he feels a kind of affinity with people who have at one time or another found themselves in strange situations. These are the kinds of people with whom De Kom regularly comes into contact during the course of his work as a forensic psychiatrist in the Pieter Baan Centre. Reflecting on the matter of the relationship that a psychiatrist has with his patients, he has published a collection of fictitious discussions between historical criminal figures, such as the emperor Nero and Osama Bin Laden, in the book Het misdadige brein. Over het kwaad in onszelf (‘The criminal brain. About the evil in oneself’). In terms of his poetic self De Kom has sometimes compared himself to a ‘white raven’. His grandfather, Anton de Kom, who spoke out in support of the slaves and the black community in Suriname, was black. Since Anton de Kom married a white woman and Antoine de Kom’s own mother was also white, the poet is much paler than many Surinamers. This subject, the matter of the different colours of the skins of the people in his family, returns in his second collection De kilte in Brasilia (‘The chilliness of Brasilia’; 1995). Even the title of the collection Zebrahoeven (‘Zebra’s hooves’; 2001) reminds one of the connection that exists between black and white.

In an interview De Kom once revealed that because of his skin colour he is often presumed to be someone who hails from the Mediterranean region. In fact it would seem that De Kom feels rather at home in those parts: his most recent collection, ritmisch zonder string (‘rhythmic no string’), includes many references to visits made to countries around the Mediterranean Sea. He has written poems in Fes, Menorca, Istanbul and Damascus that allude to the presidential Syrian family and relate to the Sahara. However, De Kom has also travelled to places such as Honduras, Cape Town and Hawaii. Just as in his previous collections, he tends to ignore traditional verse forms. On the other hand De Kom does, so he claims, deliberately try to push back the barriers of poetry. He achieves that by composing prose poems, poems that read like email messages and, for instance, through the long cycle with the title Sahara Sand comprising four-lined stanzas and incorporating drawings by Julie Dassaud. It is work that displays great dedication, however De Kom confesses to having in the past been careful not to allow the message to gain the upper hand as can often happen in Surinamese poetry. ‘With me the aesthetic always has to hit back at the ethical aspect.’

It is precisely that coming together of engagement and aesthetics, the ‘making tangible of many strange worlds by combining the sensory and powerful quality of visual language with slang and folklore’ that is so highly prized by the 2014 VSB Poetry Prize jury.

Translator: Diane Butterman

Source: from the jury report upon nomination

Sponsors